Strategizing from 7 cities across the globe

Under the Veil of Virtue: How Morality Laws Perpetuate Oppression Across the MENA Region

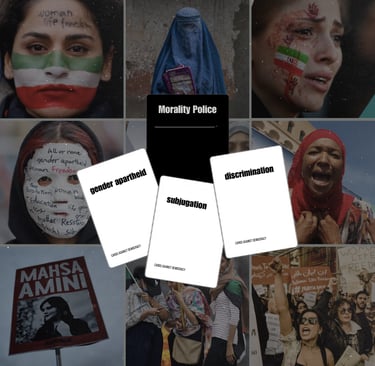

Ethicality or exploitation? Virtue or subjugation? Justice or control? At the fraught intersection of gender, religion, and politics lies a grim reality—a shadowed realm where morality is weaponized and millions are silenced to uphold the agendas of a powerful few. In this space, tradition is often wielded as a shield, and faith twisted into a tool of domination, sacrificing lives, freedoms, and futures in the relentless pursuit of control.

CIVIL SOCIETYPOLITICSINTERNATIONAL LAWDEMOCRACYMIDDLE EAST

Bassel Hijazi

11/25/20248 min read

Ethicality or exploitation? Virtue or subjugation? Justice or control? At the fraught intersection of gender, religion, and politics lies a grim reality—a shadowed realm where morality is weaponized and millions are silenced to uphold the agendas of a powerful few. In this space, tradition is often wielded as a shield, and faith twisted into a tool of domination, sacrificing lives, freedoms, and futures in the relentless pursuit of control. Beneath the guise of virtue, a systematic erosion of rights takes place, shaping a world where the sacred principles of equality and dignity are cast aside in favor of authoritarian rule.

Iran

To understand how morality laws manifest as tools of control, we begin with Iran, where the establishment of the Morality Police has institutionalized the suppression of individual freedoms under the pretense of religious and cultural preservation. The Morality Police, or ‘Gasht-e Ershad’, was established in 2005 under the Law Enforcement Command of Iran with the primary task of enforcing the hijab law and regulating public behavior according to Islamic codes. Their patrols in public spaces like streets and public transport target women, ensuring they cover their hair and dress modestly. Women who fail to comply face immediate arrest, fines, or detention in "re-education centers”, where they are forced to learn proper Islamic dress and behavior. While not officially part of the ‘Basij’ forces, a paramilitary volunteer group under the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), the Morality Police often collaborate with them to bolster enforcement. The ‘Basij’ forces, originally created during the Iran-Iraq War, now operate across Iran, including in public spaces, and are infamous for their brutality in silencing dissent and maintaining government control.

Iran’s government justifies the Morality Police’s actions by claiming that they are necessary for preserving public virtue and upholding Islamic values. However, their activities have grown into a symbol of oppression, disproportionately targeting women and severely limiting their freedoms. In addition to dress codes, the Morality Police enforce curfews on women and scrutinize behaviors like mixed-gender gatherings and even public displays of affection, often using force to break up gatherings. For example, in 2018, police detained a young woman for posting a video of herself dancing in public, an act that violated the country’s strict morality laws.

These laws have created an atmosphere of fear and control, where women must constantly navigate the threat of public shaming and violence. The arrest and death of Mahsa Amini in 2022, after being detained by the Morality Police for an alleged violation of the hijab law, sparked widespread protests across Iran. Mahsa’s tragic death ignited a powerful resistance movement, with women removing their hijabs in public to defy the system. But these acts of defiance come at a high cost. Many protesters, including women and men, have faced imprisonment, torture, and death at the hands of the Morality Police and the ‘Basij’ forces.

A female student at Tehran's Islamic Azad University recently stripped to her underwear in protest against Iran's hijab laws after being stopped by security for not wearing a headscarf. Footage showed her sitting near-nude before being violently forced into a car and taken to a mental hospital, where she sustained injuries, including heavy bleeding. Amnesty International has called for her immediate release, citing allegations of beatings and sexual violence. In response to such defiance, the Iranian government has introduced a "rehabilitation" clinic for women who refuse to wear the hijab, claiming they reject the veil due to "environmental pressures." The clinic will offer "scientific and psychological treatment" targeting women, particularly teenagers and young adults, as part of the state's efforts to suppress dissent and enforce conformity.

Despite the brutal repression, the Iranian government defends the Morality Police as crucial for maintaining public order, continuing to oppress its population under the guise of virtue. The international community has increasingly criticized Iran’s use of morality laws to maintain control, highlighting the widespread violation of human rights and the brutal tactics used by the state. The Morality Police’s actions reflect not a concern for morality, but a systematic effort to dominate and crush individual freedoms, particularly those of women.

Afghanistan

While Iran’s morality laws target individuals in the name of protecting religious values, Afghanistan under Taliban rule has entrenched a similar—but even more brutal—system of control. Since the Taliban's resurgence in 2021, Afghanistan has witnessed a relentless dismantling of women’s rights, enforced under the guise of morality and tradition. Central to this oppressive regime is the Ministry for the Propagation of Virtue and the Prevention of Vice, which replaced the Ministry of Women's Affairs. This institutional change marked the start of a systematic campaign to erase women from public life and enforce a strict interpretation of Islamic law.

Early policies targeted education and mobility. Girls were banned from attending secondary schools, and despite initial assurances, the Taliban reversed decisions to allow their education, citing the need for an "appropriate Islamic environment." Women were required to cover their faces in public, with penalties imposed on male guardians for non-compliance. Restrictions on mobility grew severe, with women banned from traveling without a male guardian or using public transportation.

Public spaces were restructured to enforce gender segregation, excluding women from parks, universities, beauty salons, and gyms. Media access also tightened, as women were banned from appearing in television dramas and female journalists were forced to wear face coverings. Prohibitions extended to women entering amusement parks and public baths, leaving no space for personal or social freedoms.

Employment opportunities for women have been systematically dismantled. A ban on women working in NGOs led to the suspension of critical aid programs. Women were excluded from roles in healthcare and education, and those working in restaurants and cafes faced dismissal. By 2023, universities were effectively closed to women, and female students were barred from taking entrance exams. Restrictions further extended to libraries, cultural centers, and even private businesses.

In mid-2024, the Taliban expanded their efforts to silence women entirely. Reports of women being arrested for speaking loudly or laughing in public emerged. Other measures targeted even the most basic forms of interaction: women were banned from speaking to each other in certain public settings. Surveillance of online activities intensified, leading to arrests for "immoral" behavior. These measures were enforced with violence and public punishments, creating an atmosphere of fear and oppression.

By 2024, Afghanistan had become a stark example of gender apartheid. Women were barred from attending social events like weddings, participating in religious ceremonies, or even being present in public spaces without a male guardian. Prohibitions extended to trivial acts such as walking alone or raising their voices in public.

The Taliban's systematic erasure of women has drawn widespread condemnation from human rights organizations and the international community. Critics have labeled these policies as a form of gender apartheid, designed to isolate women from society and strip them of autonomy. Despite growing global outrage, the Taliban continues to justify these actions under the banner of morality and virtue, leaving Afghan women trapped in a deeply oppressive regime that extinguishes their basic freedoms and humanity.

Libya and Saudi Arabia

Beyond the entrenched systems of Iran and Afghanistan, other nations in the MENA region, such as Saudi Arabia and Libya, demonstrate contrasting approaches to morality laws. While one balances reform with tradition, the other descends further into authoritarian control. These developments illustrate the varying ways morality is policed in societies grappling with modernity and tradition.

Saudi Arabia: Historically, Saudi Arabia's morality police, formally known as the Committee for the Promotion of Virtue and the Prevention of Vice, wielded extensive powers to enforce public morality. These included monitoring dress codes, enforcing gender segregation, and even arresting individuals for behavior deemed un-Islamic. However, under Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman’s Vision 2030 reform plan, the ‘mutawa’'s influence has been significantly curtailed. Their power to make arrests was revoked, and their role reduced to advisory functions, signaling a shift towards a more open and modern society. Women, in particular, have benefited from these changes, gaining new freedoms such as driving, attending public events, and traveling without male guardianship in certain circumstances. Despite these reforms, critics argue that fundamental human rights issues persist, including crackdowns on dissent and free expression, raising questions about the balance between progress and control in the Kingdom.

Libya: In stark contrast to Saudi Arabia's recent reforms, Libya’s morality laws have taken a regressive turn. In late 2024, Emad al-Trabulsi, the Tripoli-based Minister of Interior, announced the reintroduction of morality measures reminiscent of the Taliban’s approach in Afghanistan declaring that there is “no space for personal freedom in Libya”. These measures include mandatory veiling for girls as young as nine, restrictions on women’s freedom of movement without a male guardian, and heightened surveillance of public spaces to ensure adherence to conservative Islamic norms. This reimplementation has sparked fears of a broader crackdown on personal freedoms, particularly those of women.

The measures are presented as a means of preserving societal traditions, but they are widely criticized for entrenching gender discrimination. The mandated veiling of young girls and the restriction of women’s mobility not only limit individual freedoms but also institutionalize patriarchal control. Public spaces have become sites of heightened surveillance, with morality police monitoring compliance under the pretext of safeguarding cultural values. Reports have surfaced of women being harassed or detained for minor infractions, fueling an atmosphere of fear and repression.

Libya’s reintroduction of these measures comes amidst ongoing political instability, which has left the country divided and vulnerable to authoritarian policies. Conservative factions have welcomed these laws, framing them as a return to moral order, while human rights activists have decried them as tools of oppression. Amnesty International and other organizations have warned that these laws will deepen systemic inequality and further marginalize women and minorities. The international community has yet to respond with unified condemnation, leaving Libyan women to navigate this regressive environment largely unsupported.

Common Threads

The enforcement of morality laws reflects a dual strategy of combating Western influence and weaponizing religion to consolidate power. Framed as efforts to preserve cultural and religious values, governments present these measures as necessary to safeguard national identity against the perceived threat of Western liberalism. Yet beneath this narrative lies a deliberate use of religion as a political instrument to legitimize state authority, suppress dissent, and maintain control.

In Iran and Afghanistan, morality laws enforced by the morality police and ministries of virtue serve as a clear rejection of Western ideologies, particularly those advocating for gender equality and individual freedoms. The stringent regulations around women’s dress codes and public behavior are presented as defenses of Islamic values. However, they function as tools to enforce patriarchal dominance and silence opposition. Similarly, Libya’s reintroduction of morality policing under the pretext of protecting societal traditions highlights how these measures are used to reassert state authority and resist external cultural influence during periods of political instability.

This dual strategy allows these governments to position themselves as protectors of their nations' values while simultaneously weaponizing religion to delegitimize opposition and dissent. By framing morality laws as a shield against Western interference, these regimes foster a narrative of cultural and ideological resistance. At the same time, the invocation of religion consolidates internal power by equating compliance with moral and spiritual righteousness. This intersection of resisting external influence and leveraging religious authority underscores the complex role morality laws play in maintaining authoritarian control under the guise of cultural preservation.

Conclusion

While these practices are undeniably oppressive towards citizens, it's important to recognize the double standards in the global discourse on human rights. Western nations often utilize organizations like Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International to critique the human rights records of these countries, yet similar scrutiny is not always applied to their allies. For example, Israel's policies towards Palestinians have faced widespread criticism, but Western responses are often muted compared to the swift action seen in conflicts like Russia's invasion of Ukraine. Similarly, countries like Saudi Arabia and Egypt, despite their human rights abuses, continue to enjoy strong Western support due to geopolitical alliances. This selective application of human rights advocacy raises a critical question: are human rights truly a universal value, or merely a tool shaped by geopolitical interests?

References

Al Jazeera. (2021). Taliban replace ministry for women with guidance ministry.

Amnesty International. (2024). Saudi Arabia repressive draft penal code shatters illusions of progress and reform.

Amu. (2024). Taliban’s new morality laws: Oppression rooted in the 1990s returns.

AP News. (2024). Taliban’s new vice and virtue law targets women, minorities, and media.

Associated Press. (2024). How the Taliban’s new vice and virtue law erases women. New University in Exile Consortium.

Fassihi, F. (2022, September 23). Iran morality police root cause of Iranian protest anger: Explainer. Al Jazeera.

Human Rights Watch. (2015, February). Women report plan to promote virtue and prevent vice. Iran Human Rights.

International Business Times. (2024). Iran opens ominous clinic ‘quitting hijab removal’ to re-educate women who refuse to cover.

Karmon, Y. (2024). Morality police in Iran: Guardian of tradition or symbol of repression? Eurasia Review.

Overseas Development Institute. (2024). New morality law in Afghanistan: Gender apartheid.

Purtill, C. (2024, November 3). Iran student strips off and walks around in underwear in apparent protest at strict hijab laws. New York Post.

Time. (2023). Iran morality police: Mahsa Amini case highlights issues of repression.

Verity News. (2024). Libya introduces morality police to enforce traditions.