Strategizing from 7 cities across the globe

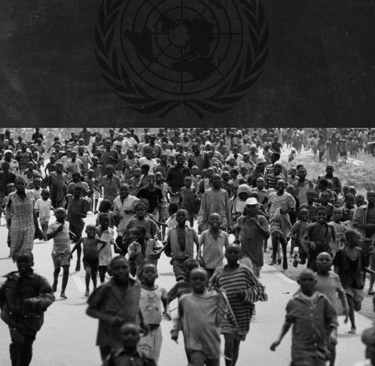

The Price of Silence: UN Intervention During the Rwandan Genocide

This paper argues that the legal obligation to intervene under the Genocide Convention remains weak without stronger enforcement mechanisms, making legal accountability limited. More generally, this paper also questions the UN’s efficiency and competency in acting against crimes against humanity, war crimes, and genocide.

WARFAREDEMOCRACYPOLITICSINTERNATIONAL LAWGENOCIDEUNITED NATIONSTRANSITIONAL JUSTICE

Michela Salama-Robino

5/30/20256 min read

Between April and July 1994, more than 800,000 civilians in Rwanda were mercilessly killed. A genocide in which two ethnic groups – the Hutus and the Tutsis – targeted each other lasted 100 days. Despite the existence of a United Nations peacekeeping mission (UNAMIR), the UN failed to react accordingly and in a timely manner.

This paper argues that the legal obligation to intervene under the Genocide Convention remains weak without stronger enforcement mechanisms, making legal accountability limited. More generally, this paper also questions the UN’s efficiency and competency in acting against crimes against humanity, war crimes, and genocide.

In this evaluative analysis, the UN’s role in its generality, the Genocide convention (with a special focus on Article l and Article VIII), the UN Charter, and UNAMIR are covered. Additionally, principles of humanitarian law, legal responsibility, and customary law are explored. Lastly, cases such as Bosnia and Herzegovina vs. Serbia and Montenegro, South Africa vs. Israel, and The Gambia vs. Myanmar are mentioned.

Contextual Overview

The Rwandan Genocide officially started on April 6th 1994, after president Juvénal Habyarimana’s plane was shot down near Kigali. Over the next approximately 100 days, extremist Hutu factions orchestrated the systematic killing of an estimated 800,000 Tutsis and moderate Hutus. Extremist Hutu militias like the Interahamwe, supported by local government officials, wielded weapons such as machetes and small arms and were incited to violence by hate propaganda spread by media such as Radio Télévision Libre des Mille Collines (RTLM).

This genocide was rooted in deep ethnic division created during the colonial rule of the German Empire in East Africa (1884-1916) and later exacerbated by Belgian rule (1916-1962), favoring Tutsi, deepening ethnic hierarchies, and putting the Hutu majority on edge. Tensions deepened in the years following independence in 1962, erupting in cycles of ethnic violence and displacement that led to the genocide in 1994.

The UN’s response during the genocide was paralyzed. The United Nations Assistance Mission for Rwanda (UNAMIR), mandated under Chapter VI of the United Nations Charter, was more suitable for peacekeeping rather than enforcement (Charter of the United Nations: Chapter VI). Although there were clear warnings — for instance, the January 1994 “Genocide Fax” by General Roméo Dallaire which informed UN Headquarters of the planned mass killings — there was no meaningful response (Dallaire). Instead of bolstering it, the Security Council cut the number of UNAMIR troops from 2,500 to a mere 270 when the violence exploded (Peacekeeping Mission in Rwanda (UNAMIR)).

It was not until late June 1994 that foreign forces dispatched under Chapter VII of the UN Charter intervened, in the form of the French-led Operation Turquoise. However, by then, the genocide was practically over, and the intervention had little effect in stopping the massacres. Operation Turquoise, in fact, has been more broadly condemned for protecting some perpetrators accidentally. Had the UN responded accordingly, hundreds of thousands of lives would have been saved. The UN’s delay raises crucial legal and moral questions on the effectiveness and enforceability of international obligations.

Legal Framework

The 1948 Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide serves primarily to provide legal support for intervention in cases of genocide. According to Article I of the Convention, State parties are obligated to prevent and punish genocide (Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide). All parties are required to take action when there is credible evidence or threats of genocide, as it is codified as a crime under international law.

Under Article VIII, the UN Institutions are empowered to take action in accordance with the Charter of the United Nations (UN Act) to prevent and put an end to genocide (Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide). However, this article was of no use in the Rwandan case due to its vagueness and lack of clear procedural requirements and expectations for immediate action.

The UN Charter's Chapter VI addresses peaceful conflict resolution and prohibits the use of force, causing difficulties in managing this situation. Consequently, UNAMIR operates under the Charter. The inclusion of acts of aggression, breaches of peace, and threats to peace in a Chapter VII mandate would have resulted in increased involvement.

Additionally, according to customary international law and the Draft Articles on Responsibility of States for Internationally Wrongful Acts, preventing genocide is a duty that is supported by evidence. In the ICJ case of Bosnia and Herzegovina vs. Serbia and Montenegro (19 September 2000), it was confirmed by Serbia and Montenegro that states must take action to prevent genocide when they have the ability to influence the actors (International Court of Justice). While it is not clear how often this obligation should be activated, the principle emphasizes that failure to act in the light of explicit warning may constitute a breach.

The combination of these tools reveals the conflict between the ethical concerns of preventing genocide and the legal options available.

Legal Analysis and Application

Political activism was not a prerequisite for legal compliance in the Rwandan Genocide. This is due to the fact that UN member states were obligated to prevent genocide under Article I of the Genocide Convention, and this obligation may have been instigated by early warnings, such as General Dallaire's "Genocidal Fax".

However, this duty was not followed. The UN Security Council's decision to weaken UNAMIR instead of strengthening it in the face of escalating violence indicated a disregard for the Genocide Convention. Why would the Genocide Convention be disregarded? The answer is nuanced; although intended to trigger collective action, article VIII was never effectively applied in a manner that resulted from meaningful intervention. Even though the Security Council did not immediately respond, despite calls from within the UN and humanitarian groups, it was too late — and article VIII’s ambiguity does not excuse the inefficiency in inaction from the UN Security Council.

The case of Bosnia and Herzegovina v. Serbia and Montenegro provide a precedent for evaluating Rwanda. Cases like The Gambia v. Myanmar and South Africa v. Israel demonstrate an increasing awareness that international legal responsibility can be inflicted beyond just direct participation, but also to non-action, equating to similar violence (International Court of Justice). Despite the states' capacity and awareness, Rwanda experienced a political and legal failure due to their unwillingness to authorize strong intervention.

Temporary intervention in the UN is hindered by a political structure, particularly the veto power of permanent Security Council members. Where clear legal and moral obligations exist, the distinction between the UN as an institution and its member states cannot be disregarded. The Convention's principle mandates preventive measures despite the lack of specific procedures for enforcement.

Hence, the failure in Rwanda is due to legal deficiencies, absence of enforcement mechanisms, and political disinterest. Enhanced global legal frameworks must include provisions that enable swift enforcement of genocide warnings in the early stages. There is an urgent need for attention.

Implications and Lessons

The Rwandan Genocide prompted an urgent review of international legal principles and intervention methods. In 2005, the absence of action led to a shift towards the Responsibility To Protect (R2P) doctrine, which mandates international intervention through diplomatic, humanitarian, and military means when aimed at protecting citizens from genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing, or crimes against humanity (Responsibility to Protect).

Nonetheless, R2P is more of a political promise than an official decree; there is no legal authority to force action, and its application is still inconsistent. In Rwanda, it is taught that normative changes must be accompanied by institutional readiness and legally binding structures.

The ongoing challenges, such as those faced in Myanmar and Gaza, highlight the fact that while there is a lot of legal rhetoric, geopolitical interests often take precedence, and humanitarian urgency is forgotten. Legal obligations to prevent genocide necessitate the establishment of distinct threshold measures, automatic triggers for action, and robust international support mechanisms.

Rwanda's experience demonstrates that international law must adapt to both aspirational principles and actionable mandates. Without enforcement capacity, the promise of "never again" is merely symbolic— not effective.

Conclusion

The Rwandan Genocide remains one of the most significant failures of global intervention in recent history. Mass atrocities were not prevented due to the absence of political will and enforcement mechanisms under the Genocide Convention. Although the current framework of international law offers moral and legal basis for intervention, structural reforms are not sufficient to provide effective means of enabling intervention in any given situation.

Strengthening the Genocide Convention with mandatory response protocols, enhancing the authority of international courts, and reforming the UN Security Council's veto system are essential steps toward ensuring genuine accountability. Rwanda's bloody history demands more than remembrance—it requires legal transformation. Only through enforceable mechanisms and principled leadership can the international community hope to uphold its humanitarian duty to protect vulnerable populations.

Download the Full Document

References:

"Charter of the United Nations: Chapter VI." United Nations, www.un.org/en/about-us/un-charter/chapter-6.

"Charter of the United Nations: Chapter VII." United Nations, www.un.org/en/about-us/un-charter/chapter-7.

"Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide." United Nations, www.un.org/en/genocideprevention/documents/atrocity-crimes/Doc.1_Genocide_Convention.pdf.

Dallaire, Roméo. Shake Hands with the Devil: The Failure of Humanity in Rwanda. Arrow Books, 2004.

International Court of Justice. Bosnia and Herzegovina v. Serbia and Montenegro. 26 Feb. 2007, www.icj-cij.org/en/case/91.

International Court of Justice. Application of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (The Gambia v. Myanmar). www.icj-cij.org/en/case/178.

International Court of Justice. Application of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (South Africa v. Israel). www.icj-cij.org/en/case/192.

"Peacekeeping Mission in Rwanda (UNAMIR)." United Nations Peacekeeping, peacekeeping.un.org/en/mission/past/unamirS.htm.