Strategizing from 7 cities across the globe

The Golden Age of Capitalism: The Social Consequences

Labubus, “Alo, Pilates, Matcha”, and the “Old money” style, are not simply humorous trends to follow or criticize, but are also incredibly significant and loaded symbols of the economic condition we’re currently in. It might be odd to think that what may seem like harmless fashion and lifestyle trends can directly correlate with a far more serious topic that is economic philosophy, and yet… it does.

SOCIOLOGYDEMOCRACYMENTAL HEALTHECONOMIC PHILOSOPHYANTHROPOLOGY

Chloé El Khoury

9/1/20259 min read

What is class consciousness and why is it important ?

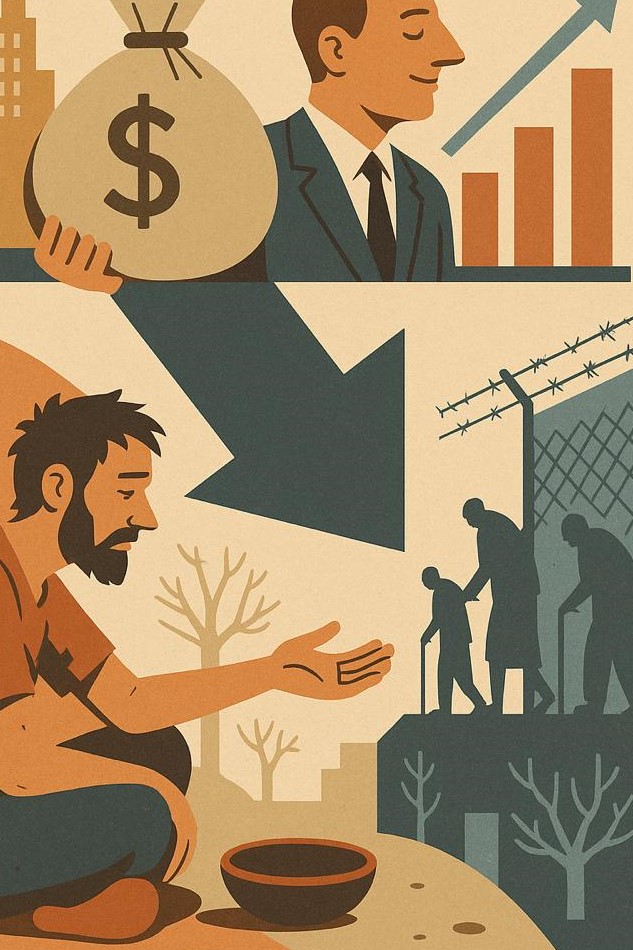

By definition, class consciousness is a term from both sociology and political theory that refers to the awareness by a social class of its own economic position, interests, and shared identity as a group. So, when people understand that they belong to a particular social class (e.g., working class, middle class), and recognize that they have common interests and challenges (like wages, working conditions, social rights), then they become more likely to organize collectively (unions, political parties, manifestations) to defend or advance those interests. In simpler words, it is when one becomes aware of the economic and social class they belong to, the struggles it faces, and the rights or changes it may need. It’s also realizing that one's struggles are not individual, they’re collective. It is how history has always unfolded itself, beginning with the French Revolution of 1789. In fact, Karl Marx himself said in The Communist Manifesto of 1848 that “the history of all existing society is the history of class struggles”. Without class conflict, history would almost stop.

Today, particularly in Lebanon, class consciousness is considered almost non-existent. There have been few expressions of class consciousness among the Lebanese people, such as the 2019 Thawra (Arabic for “revolution”), which erupted after the near-imposition of a WhatsApp tax. However, even that movement struggled to address deeper class divisions. In fact, in Lebanon, when people speak of revolution or protest, the focus tends to be on sectarian, religious, or political identities. Even when protests begin with economic concerns, they quickly shift towards the difference that Lebanese brains are wired to focus on, sectarianism. Class conflict is rarely acknowledged as a driving force. Individuals often feel a strong sense of belonging and identification with their religion,and by extension with the political party that best defends it. Meanwhile, identification with social class remains weak or absent, making the traditional left–right political spectrum nearly irrelevant in the Lebanese context.

A Shiite earning below the minimum wage might gladly follow the multi-millionaire Nabih Beri and his Amal Movement, simply because they share the same religion, even though their living conditions couldn’t be more different. Similarly, a Maronite living under the poverty line might firmly back the Kataeb Party or the Lebanese Forces, even if they fail to address their daily economic hardships. In both cases, religious identity often outweighs economic class when it comes to political loyalty. This dynamic shields political leaders from scrutiny and allows them to remain unquestioned. Moreso, political leaders will often accentuate religious differences in Lebanon to distract people from the real issue: the massive economic inequalities faced among the Lebanese people. By promoting the idea that religious groups will always have opposing interests, they distract and divert attention from the common ground we all share: the economy, which underpins all other issues.

Glamourizing Lebanon, the hidden truth behind it all

The stereotypical materialism and superficiality among Lebanese people have been normalized — even romanticized — to the point of becoming an internet joke. In reality, however, the widespread tendency to fake a certain lifestyle in order to project an image of a higher social status, regardless of one’s actual conditions, holds far more serious and far-reaching consequences than people often realize. In the simple move of wearing “fake” luxury brands to appear wealthier, rather than acknowledging their true social class and unite with others in the same economic situation to demand better rights, people unintentionally block any real path towards general progress, which can affect multiple generations among multiple areas.

The reality of Lebanon is much less glamourized than what we tend to see on social media. According to a new World Bank report, the share of individuals in Lebanon living under the LHS poverty line has more than tripled over the past decade reaching 44% of the total population in 2024. Not only did the share of poor Lebanese rise between 2012 and 2022, but so did the depth and severity of their poverty. In 2012, poor Lebanese needed an average of 3% of the poverty line to escape poverty; by 2022, this amount rose to 9.4%. In 2022 and 2023, 56 percent of Lebanese households reported that they felt either poor or very poor compared to 19 percent in 2011 and 2012. The rise in monetary poverty seen in Lebanon reflects a lack of economic growth in a country where the new 2025 minimum wage is only 312 dollars per month. Overall, people’s consumption shrank by about 32% in ten years, with the poorest losing more than the richest.

Notably, the gap between the consumption levels of the richest and poorest individuals in Lebanon between 2012 and 2022 remained relatively unchanged, highlighting that the inequalities are not simply a result of the 2019 economic crisis. Rather, these inequalities were already deeply rooted in a system that was never designed to question them.

The social consequences of such a system

A. The hyper-Individualization of society

Individualism itself is not inherently negative. In fact, it was individualist thinking that empowered people in the 18th century to challenge monarchies and demand fundamental rights such as freedom, equality, and self-determination. These values helped lay the foundation for modern democracy and human rights. However, it is individualism in its extreme form that becomes harmful to the well-being of society.

When people don’t feel a sense of community within their own social class, there tends to be a phenomenon known as the “hyper-individualization of society”, which is a social process in which people increasingly see themselves as independent individuals rather than as members of traditional groups such as families, religious communities, or social classes. People are then expected to shape their own lives, identities, and destinies independently, rather than being guided by traditional collective structures – leading to an overwhelming burden placed on “personal responsibility”. According to key thinkers like Ulrich Beck and Zygmunt Bauman, the individualization of society is a direct consequence of capitalism, driven by the personalization of working conditions and the loss of collective awareness. It’s almost as if each job is uniquely tailored to the individual, to the point where no one else can truly relate when a person speaks up about their struggles, ultimately isolating people in their professional hardships.

In Lebanon, although citizens don’t usually feel a strong sense of community based on their social or economic class, they continue to experience a deep sense of belonging within their families and religious groups. As a result, this hyper-individualization of society is far less visible in Lebanon compared to Europe, for instance, where traditional social bonds such as family and religion have significantly weakened.

This contrast might help explain why Lebanese people often appear more joyful or resilient, even amid economic collapse or political instability, while Europeans, despite more stable conditions, may report lower levels of happiness or fulfillment.

But to go back to hyper-individualization as a global universal effect, in such an era, people are led to falsely believe that anyone can become whoever they want, regardless of their background — and that if they don’t succeed, it’s entirely their fault, as though everyone had the same opportunities. Because social bonds are broken and individuals no longer belong to a supportive group that would come to defend them, individuals then internalize their own failure purely as a personal fault, even if the system was never meant to see them win, nor designed for them to succeed in the first place. With common beliefs such as ‘personal success is entirely within individual control and depends solely on personal effort’, or that ‘anyone can rise to any position regardless of their starting point’, such misconceptions completely disregard systemic barriers and structural inequalities, leading to unfair judgments.

An enormous propaganda machine fuels this narrative, emphasizing messages like “It’s all up to YOU now— the ball’s in your court; you can become whoever YOU want.” It romanticizes work by highlighting rare success stories such as the creator of Alibaba who was once fired from McDonald’s, as if these exceptions were the norm. But what about the countless other McDonald’s employees whose chances were never in their favor? In line with this rhetoric, their struggles are simply their own fault.

According to French sociologist Louis Chauvel, by convincing people that we live in a classless society where everyone has equal opportunities to become whoever they want, the system deprives the most disadvantaged of any meaningful and positive sense of collective belonging. The emphasis on becoming the “master of one’s own choices” through individualization mainly benefits the privileged classes. Without the ability to share their collective experience, those left behind are led to believe that their failures are entirely their own fault, which contributes to higher rates of depression and loneliness within society. Moreso, in such a system, people begin to prioritize their own well-being, while becoming increasingly indifferent to the suffering of their fellow citizens in a system where everyone is left to fend for themselves

: it’s the dangerous rise of indifference towards others.

The danger in such systems is that humans, by nature, were never meant to be this lonely. Biologically, biblically, psychologically, and historically, humans were always meant to live in community, evolving as social animals. Our ancestors survived not because they were the fastest or strongest, but because they cooperated — in hunting, raising children, protecting one another, and sharing resources. Isolation, in evolutionary terms, often meant death. Moreso, social connection is a basic psychological need, with studies showing that loneliness can be as damaging to health as smoking or obesity. Humans thrive on love, friendship, recognition, and support. Since the beginning of time, all known human cultures — from tribal societies to modern cities — are built around structures of community, whether family, clan, village, religion, or nation. No one is entirely self-sufficient. From food production to emotional support, humans rely on others. So, the myth of the ‘self-made’ person—promoted by capitalist propaganda to create human machines consumed by labor, whose value is measured solely by their productivity —ignores centuries of human history that show we are meant to live, grow, and survive together.

Nowadays, in our hyper-individualist culture, by being so overly obsessed with personal success and desires, what’s best for the community is no longer on our minds, losing any sense of collective responsibility and leading to a dangerous form of narcissism. But why is so much of this success we seek, just the acquisition of material possessions? Which leads us to the second consequence…

Overconsumption and the loss of identity

The golden age of capitalism has also led to a deeper social consequence: the loss of authentic identity. While hyper-individualism remains relatively weak in Lebanon because of strong familial and religious bonds, the crisis of personal identity is, conversely, deeply rooted in the Lebanese psyche. Internet jokes often fly around about how all Lebanese people look the same, but beyond the humor, this issue runs much deeper.

Consumerism is an economic and social system that encourages the consumption of goods and services as a means of attaining well-being and happiness. Since capitalism thrives on consumption, it pushes the idea that you can buy who you want to become. Want to be a “Pilates girl”? Then purchase the pink matching workout sets — actually attending Pilates classes and becoming good at it are just secondary details. Want to appear as if you come from generational wealth? Then adopt the “old money” aesthetic, regardless of your real background. In this system, identity is no longer something we build through experience or character — it’s something we construct through aesthetics and consumption. “Clean/coquette/it girl”, “pink Pilates princess”, “office siren”, so much of identities is rooted in consumption without any real meaning. Any sense of individuality online is just spoon fed by advertising companies. The irony in this is that in some cases, people often follow a trend to feel like they’re part of something larger, which reassures them, especially in an era where, as previously mentioned, we are notoriously lacking any real sense of community.

There is a growing confusion between becoming someone and buying into the version of that person. Strip away the material signs, and identity feels empty, as if it no longer exists without consumer proof. Our personalities are overshadowed by the objects we own, reducing identity to a curated, market-driven illusion. In such a system, you are no longer a human being but a product to sell, an aesthetic to promote, an illusion to keep up with, to the point where it becomes utterly dehumanizing. This leads to an identity crisis, as we come to lose sight of who we truly are beyond what we consume.

Hyper-individualism and overconsumption are ultimately related. For instance, this form of narcissism talked about is also shown in manifestation culture, where we talk a lot about how to get everything we want from this world, but not about how to give your best to the world. It is also seen in celebrity culture where prominent culture icons used to be activists and leaders of social change. Now, all we have are musicians and internet personalities who rarely, if ever, speak out on global or local injustice but are quick to sell you anything. It is also seen in modern liberal feminism, where the new trend is to be a powerful girlfriend who demands material possessions from her partner as a reflection of self-worth. This disguises consumerism as empowerment, with phrases such as “run, don’t walk,” “you NEED this,” or the normalization of “retail therapy.” The end goal is not liberation, but possession.

In such systems, it is entirely normal to feel uneasy, depressed, lonely, and perpetually unsatisfied. The goal is not to blame individuals for falling into the trap, but rather to raise awareness of how the system operates

– so that we may begin to question it, challenge it, and ultimately, change it.

Download the full document

references

Aoun Signs Decree on Minimum Wage Increase for Private Sector.” L’Orient-Le Jour, 27 Apr. 2023, https://today.lorientlejour.com/article/1470311/aoun-signs-decree-on-minimum-wage- increase-for-private-sector.html.

Bauman, Zygmunt. Liquid Modernity. Polity Press, 2000

Beck, Ulrich, and Elisabeth Beck-Gernsheim. Individualization: Institutionalized Individualism and Its Social and Political Consequences. SAGE Publications, 2002

Chauvel, Louis. “Le retour des classes.” Revue de l’OFCE, no. 79, 2001, pp. 315–342. Cairn.info, https://shs.cairn.info/revue-de-l-ofce-2001-4-page-315?lang=fr

Lebanon Poverty More than Triples over the Last Decade, Reaching 44% under a Protracted Crisis.” World Bank, 23 May 2024, https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press- release/2024/05/23/lebanon-poverty-more-than-triples-over-the-last-decade-reaching-44-under-a- protracted-crisis.

World Bank. Lebanon Economic Monitor: Spring 2024 – Tides Yet to Turn. 24 May 2024, https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/099052224104516741/pdf/P176651-325da1d8- f439-48a7-ab6b-ae97816dd20c.pdf.