Strategizing from 7 cities across the globe

Health Equity in Lebanon: The Degree of Accommodation of Migrant Workers in the Weakened Lebanese Health Equity System

This article explores the Lebanese health equity system’s accommodation of migrant workers who have been brought to Lebanon for the purpose of domestic work or general labor. The research and analysis focus on the physical and mental health needs of migrant workers upon their arrival in a foreign country, while simultaneously forming potential improvements that the health equity system in Lebanon could implement based on these explored needs.

ROOTSHEALTHCARELAWCIVIL SOCIETYBIOLOGYINEQUALITIES

Melania Tohme

1/9/202614 min read

The failures of the Lebanese government and its predecessors have severely endangered the health security of all migrants residing in the Republic of Lebanon. Though the Lebanese Ministry of Public Health has created a Public Policy plan called “Vision 2030” (Republic of Lebanon Ministry of Public Health, 2025), the remaining gaps in Public Health Policy highlight the urgent need to address this systemic failure. Legally, the United Nations defines a migrant worker as “a person who is to be engaged or has been engaged in a remunerated activity in a state of which he or she is not a national” (OHCHR, 1990). According to the International Organization for Migration, there are currently 176,504 migrant workers present in Lebanon (2024). Therefore, migrant workers make up a significant part of the Lebanese population, with an estimate of 22% to 35% of the population consisting of migrant workers alone (International Labor Organization, 2022). Due to a significant amount of the Lebanese population being composed of migrant workers, the Lebanese Labor Laws also apply to them (Elisabeth Longuenesse, 2014). This includes being eligible to benefit from social security, which provides healthcare coverage. However, this coverage only applies to five countries, and in the case of a migrant worker being from another country than the five countries listed, it is the responsibility of the employer to cover the cost of medical insurance (Elisabeth Longuenesse, 2014). In order for any individual with residency to receive healthcare, it heavily depends on the accommodation of the health equity system of their host country. Due to the recent crises that have occurred since 2019, Lebanon’s health equity system has experienced a severe imbalance based on financial and social class. The Lebanese health equity system, though praised for its high-quality service and advanced technology, is only available to those who are able to purchase private healthcare (Aoun & Tajvar, 2024). Migrant workers cannot afford to have insurance through the private healthcare sector in Lebanon themselves, and their employers are exclusively required to provide private healthcare in the case of “work-related accidents” as per the Lebanese Labor Law (Doctors Without Borders, 2023). This article will examine the physical and mental health needs of migrant workers, and the resulting degree in which the Lebanese health equity system is equipped to provide for migrant workers. Moreover, this article will be concluded with the provision of a critical assessment as to how the Lebanese health equity system can improve.

The first key aspect of accommodations expected to be provided by the Lebanese health equity system for migrant workers are their physical health needs. In order to be able to work properly, high-quality healthcare is a necessity for migrant workers since most of the tasks completed in their jobs fall under manual labor with occupational risks (Mucci et al., 2019). Migrant workers are constantly exposed to physical injuries such as broken limbs and work-related accidents. However, the rest of the physical health needs of migrants are often overlooked, and many have other physical health problems, which have occurred from their strenuous work or poor housing conditions. For example, infectious diseases, such as parasitic infections, were found to be very common in vastly different domains of migrant work in a study done in the United Arab Emirates, a nation with close proximity and similar situational occurrences (Mucci et al., 2019). Higher intestinal infections caused by parasites and bacteria were discovered to be a common physical health dilemma among migrant workers, with 29% of household workers being infected with Trichiura, 24% of farmers and 30% of drivers being infected with Giardia lamblia, and 41% of pastors and 67% of food handlers being infected with Entamoeba histolytica or Escherichia coli (Taha et al., 2013). All of these can cause significant abdominal pain, among many other symptoms if not treated, making it extremely painful for migrant workers to work and partake in daily tasks effectively. Mortality by infectious disease is a major problem in public health, particularly in developing countries such as Lebanon (Mucci et al., 2019). Other diseases, such as Tuberculosis and Malaria, are also a significant risk to migrant workers, especially in the Middle East and in parts of Africa and Southeast Asia, where containment of these diseases and access to their treatments are scarce (Mucci et al., 2019). Migrant workers are also more prone to contracting sexually transmitted diseases, such as HIV, due to their unstable work situations, lack of access to contraception, and physical isolation (Mucci et al., 2019). This is especially prevalent in Lebanon, as there is a lack of access to HIV awareness and treatment due to social stigmas and taboos (Anera, 2012). As explained, this partly has a mental component as well, displaying how intertwined the physical and mental health needs of migrants are, and how important it is for the public health equity system to provide such needs in order to prevent both physical and mental ailments.

Another physical health disparity in the Lebanese public health equity system, particularly among female migrant workers, is prenatal care and delivery services. Migrant workers are in greater need of these health services and have a greater risk of mortality due to the severe lack of them (Molina et al., 2023). The reason why prenatal care and pregnancy are disputed in Lebanon is due to the fact that most contracts for domestic migrant workers in Lebanon, provided to them by their employers, state that they are prohibited from getting pregnant and having children (Fernandez et al., 2023). Despite this clause being present, many migrant workers still need prenatal and pregnancy care to avoid complications for the mother and the unborn child. However, this clause and the complex laws of citizenship for newborn children born to a non-Lebanese father in Lebanon prevent migrant women from seeking the care they need, as they are increasingly scared of their status of legality and pregnancy being found out by authorities (Molina et al., 2023). Thus, pregnant women spend fewer days in the hospital for prenatal care and deliveries, and are less likely to approach hospitals, clinics, and other healthcare centers for help regarding prenatal care and safe delivery (Molina et al., 2023). For example, a recent study compared Lebanese women to Syrian women, Palestinian women, and Migrant women living in Lebanon regarding prenatal and delivery services. Lebanese and Syrian women had similar statistics, with the risk of secondary complications in childbirth being almost the same. However, Palestinian and other Migrant workers were found to have much greater risks for a wide variety of serious complications in childbirth (McCall et al., 2023). Therefore, not only does the public health equity system in Lebanon fail to provide care for pregnant migrant workers, but also the domestic laws of Lebanon, which make it increasingly difficult for migrant workers to get the care they are promised under the United Nations Network on Migration and World Health Organization (United Nations Network on Migration, 2025).

Additionally, not just sexually transmitted diseases display this relationship between the physical and mental health needs of migrants. There has been a rise in obesity, hypertension and cardiovascular diseases among migrant workers, which has been notably caused by the almost instantaneous transition from developing countries to more developed countries (Mucci et al., 2019). Consequently, stress from the change in lifestyle leaves migrant workers at an increased risk for both diseases. A combination of the reduction of nutritious meals in developed countries, poor physical activity, and the stress coming from their labor-intensive jobs is responsible for this increased risk for migrant workers (Martin & Francis, 2016). Increased alcohol consumption was also found to be prevalent among migrant workers, as they struggle to adjust mentally to the new work conditions, climate, and personal expectations from their employer and themselves (Mucci et al., 2019). There is also a rising problem in the workers’ basic lifestyle needs to maintain their physical health and mental health. One of these is the drastic absence of adequate sleep, with many having very long work hours, which in turn affects their physical and mental performance significantly (Mucci et al., 2019). Diets of Migrant Workers have also seen a significant shift towards polyunsaturated fat majority diets, with a reduction in important saturated fats and complex carbohydrates, which can be detrimental for physical and mental health as well (Mucci et al., 2019). All in all, migrants are much more susceptible to physical ailments in Lebanon due to the roles and expectations their jobs require. The high rates of acute and chronic diseases, sexually transmitted diseases, complications in pregnancy and childbirth, and poor lifestyle factors display the significant gap in Lebanese Public Health Policy and the failure of the state to accommodate migrants' physical needs.

The second key aspect of accommodations expected to be provided by the Lebanese health equity system for migrant workers are their mental health needs. As stated in the above paragraphs, mental health is strongly intertwined with physical health. If a health equity system fails to keep the mental health needs of those especially prone to mental ailments in check, their physical health will deteriorate in multiple aspects. To put this into perspective, around one in three people across the globe with a chronic physical health condition also has a mental health condition, and physical illnesses greatly increase the risk of developing psychological health problems (Mental Health Foundation UK, 2022).

Unfortunately, migrant workers are more prone to “serious, psychotic, anxiety, and post-traumatic disorders” because of a complex array of socio-environmental factors (Mucci et al., 2019). In fact, in Nicola Mucci’s 2019 systematic overview, it is found that while male migrant workers are more prone to physical injury due to labor strenuous jobs, female migrant workers are more likely to develop a mental health illness due to many factors such as distance from their families, caregiver jobs, and a much larger frequency of harassment (Mucci et al., 2019). There is also the case of overqualification that can affect mental health, in which a migrant worker is placed in a job which they are overqualified for but have no choice in order to sustain their lives. This causes many symptoms, which threaten mental health, such as anger, irritability, and emotional distress (Mucci et al., 2019).

Specifically, in our region, it was found that migrant workers had an increased risk of depression and suicidal actions, and out of all categories of migrant workers, domestic migrant workers are more prone to abuse and harassment (Mucci et al., 2019). Furthermore, in a study by Dr. Nada Zahreddine discussing psychiatric morbidity in migrant workers in Lebanon, 12.5% of them had experienced sexual abuse, 37.5% physical abuse, and 50% verbal abuse. Of those migrant workers, 66.7% were diagnosed with either mental illnesses or physical illnesses on account of mental health issues (Zahreddine et al., 2013). These include psychotic episodes, anorexia, catatonic features, and delusion of pregnancy, which is a condition that migrant workers fear due to their agreed contracts as domestic workers in Lebanon (Zahreddine et al., 2013). Most shocking of all, the mean hospital stay for these migrant workers was only 13.1 days (Zahreddine et al., 2013). Usually, psychiatric care for patients experiencing serious mental health illnesses should be much longer. An example of this is anorexia treatment, with the recommended span of treatment being up to 9 to 10 months, combined with other treatments such as therapy sessions and nutritional support (NHS UK, 2024).

Unfortunately, medical treatment for migrant workers, especially mental illness treatment and support, is severely limited in Lebanon (MSF, 2025). In fact, many employers in Lebanon decide to deny the right to healthcare to the migrant workers that they employ (MSF, 2025). Even if not bound by their employers, migrant workers wishing to seek healthcare on their own accord are most often denied treatment from Lebanese hospitals due to the absence of legal documents or because they are not Lebanese (MSF, 2025). In addition, migrant workers are at an increased risk of being pursued by law enforcement in Lebanon, which incites fear and leads to them choosing not to go to a hospital or clinic for physical or mental health care (MSF, 2025). The language barrier is also an obstacle for migrant workers. Many come from countries that do not speak Arabic, Lebanon’s native language, and migrant workers often learn gradually from living in Lebanon. However, in Lebanon, in order to get the needed documents to obtain access to healthcare, documents in Arabic and proficiency in Arabic are required to understand and sign these documents, which is a language that many migrant workers do not have basic proficiency in (MSF, 2025).

All of these factors demonstrate the immense collapse of the Lebanese Public Health Equity System in terms of both physical and mental health care. It is a migrant worker’s right to receive healthcare, no matter their nationality, according to the UN Office of the High Commissioner (OHCHR, 2013). This is especially true when it comes to emergency care. Instead, migrant workers are forced to live in fear, as running away will often lead them to be homeless and stranded in an unfamiliar country with no documents or funds to go home (MSF, 2025). Those who do manage to escape can only rely on private companies and NGOs, such as MSF, Caritas, and special homeless shelters dedicated to migrant workers (MSF, 2025). This leaves migrant workers at the bottom of the system, which dismantles the meaning of equity at its core and dehumanizes workers who support many households and companies across the country.

If the Lebanese Public Health Equity System is not up to par, how can it be altered and reshaped for the better? To start on a private level, employers and companies can take adequate steps to ensure that health-related issues on a small scale do not pose a risk to migrant workers. This includes stocking products for hygiene and making them readily available, and providing a place to sanitize and wash up, especially when it comes to handling food (Mucci et al., 2019). Employers can take greater precautions for their workers, and take them to regular checkups, as well as do paperwork on their behalf.

Unfortunately, this does not fix the Public Health Equity System; it just sustains health practices in a broken system. To truly fix the system, there must be reform on a policy level. For physical and mental health illnesses, reforms on laws such as legal documentation requirements for migrant workers in Lebanese hospitals, abolishing harmful systems that force migrant workers to sign unfair clauses that strip them of their health rights, and taking more action on stigmatized physical health problems, such as HIV and sexually transmitted disease treatment, are necessary (Mucci et al., 2019). Enforcing labor laws for migrant workers, such as mandated work hours and hygiene in workplaces, would greatly strengthen the public health equity system in Lebanon (Mucci et al., 2019). Policy innovation is another key need to reform the system. Now that new diseases and new health crises are emerging, many are at risk, especially migrant workers. Inviting young students to help innovate and create new policies for the Lebanese health equity system alongside the government not only brings more awareness for migrant worker health, but it also engages the youth of Lebanon in much-needed change in the country (Kak et al., 2025).

Another core aspect of improving the Public Health Equity System is mobilizing government or NGO funded clinics all over Lebanon with adequate resources to treat both physical and mental health illnesses. Due to the fund crisis in the Lebanese government, this could be powered by donations for NGOs, independent organizations, and donors from the Lebanese diaspora willing to support the structural reform of the health equity system, especially for those who cannot afford to go anywhere else but a mobilized walk-in clinic, such as migrant workers (Kak et al., 2025).

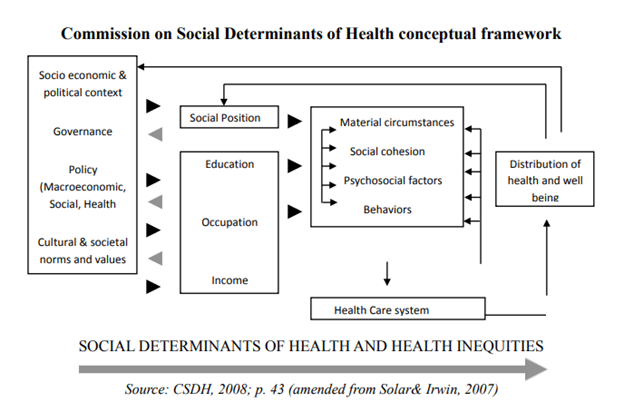

However, health equity is a more complex issue, especially in Lebanon. There are many social determinants associated with improving a run-down public health equity system. As illustrated in this diagram by the WHO Commission on Social Determinants of Health, it not only occurs with policy reforming and change-making (CSDH, 2008).

The Public Health Equity System, and the reception of the individual, depends heavily on individual factors as well, such as social position, education, occupation, and income. Since migrant workers usually fall to the bottom in these categories, it is much harder for them to obtain resources and treatment. It is the responsibility of the Ministry of Public Health, along with NGOs and other private networks, to use data collected to serve this bottom percentile. Without recognition of all of these traits as a system, the Public Health Equity System will always be doomed to fail. Thankfully, the Ministry of Public Health, in their 2030 plan, will be targeting public health equity. However, it is up to the citizens of Lebanon to hold the government accountable and to stand up for those who do not have access to the same healthcare that we do in the system.

In conclusion, the Lebanese Public Health Equity system has repeatedly failed to cover and stand up for migrant workers. Migrant workers who come to Lebanon are bound by an outdated legal framework, and therefore do not seek out healthcare as frequently as the average Lebanese citizen, or do not seek it out at all in fear of being captured or deported. Therefore, migrants are at an increased risk of contracting physical health ailments, such as Tuberculosis, Malaria, HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases, and nutrient deficiencies. They are also at an increased risk of developing mental health ailments, such as anorexia, depression, and PTSD from abuse inside their workplaces. The Lebanese Public Health Equity System must reform based on a complex system of social determinants and must provide healthcare for even the most vulnerable in the form of policy reform, mobilization of resources and clinics, and engagement with the youth. The Lebanese citizens must also be aware of the plan the Ministry of Public Health has, and must hold them accountable for implementing this plan, as migrant workers are not able to stand up for their own rights in a country that does not defend their rights.

Download the full document

references:

Aoun, N., & Tajvar, M. (2024, September 27). Healthcare delivery in Lebanon: A critical scoping review of strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats. BMC health services research. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11429949/#Abs1

Assessment of Labour Migration Statistics - Lebanon ... (2022a, March 9). https://www.ilo.org/media/569631/download

El Kak, F., El Fakahany, S., Kabakian-Khasholian, T., McCall, S., & Saad, G. (2025, July 28). Health policy challenges in Lebanon’s healthcare system: on sexual and reproductive health and rights. Taylor & Francis Online: Peer-reviewed journals. https://www.tandfonline.com/

Fernandez, B., McGee, T., & Block, K. (2023, July 27). At Risk of Statelessness: Children Born in Lebanon to Migrant Domestic Workers. Sage Journals. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/328039672_httpjournalssagepubcomdoiabs1011770887302X07303626

Granero-Molina, J., Gómez-Vinuesa, A. S., Granero-Heredia, G., Fernández-Férez, A., Ruiz-Fernández, M. D., Fernández-Medina, I. M., & Jiménez-Lasserrotte, M. del M. (2023, June 5). Sexual and reproductive health care for irregular migrant women: A meta-synthesis of qualitative data. MDPI. https://www.mdpi.com/2227-9032/11/11/1659

Helping HIV patients in Lebanon. Anera. (2012, January 21). https://www.anera.org/stories/helping-hiv-patients-in-lebanon/

Hoda, T., Soliman, M., & Banjar, S. (2012, December 19). Intestinal parasitic infections among expatriate workers in ... Intestinal parasitic infections among expatriate workers in Al-Madina Al-Munawarah, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. http://msptm.org/files/78_-_88_Hoda_A_Taha.pdf

International Convention on the Protection of the rights of All Migrant Workers and members of their families | ohchr. (1990). https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/international-convention-protection-rights-all-migrant-workers

Lebanon National Health Strategy – Vision 2030. (2025). https://www.moph.gov.lb/userfiles/files/About MOPH/StrategicPlans/National-Health-Strategy–Vision2030/NHS-2-yr review[1].pdf.pdf.pdf

Longuenesse, E., & Tabar, P. (2016, April 20). Migrant workers and class structure in Lebanon,. shs. https://shs.hal.science/halshs-01305367v1

Martin, M., & Francis, L. (2016, December 18). U.S. migrant networks and adult Cardiometabolic Health in El Salvador. Journal of immigrant and minority health. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27137525/

McCall, S. J., El Khoury, T. C., Ghattas, H., Elbassuoni, S., Murtada, M. H., Jamaluddine, Z., Haddad, C., Hussein, A., Krounbi, A., DeJong, J., Khazaal, J., & Chahine, R. (2023, February 22). Maternal and infant outcomes of Syrian and Palestinian refugees, Lebanese and migrant women giving birth in a tertiary public hospital in Lebanon: A secondary analysis of an obstetric database. BMJ open. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9950922/#abstract1

Migrant presence monitoring iom Lebanon. (2022b). https://dtm.iom.int/sites/g/files/tmzbdl1461/files/reports/MPM_Report_Round%204.pdf

Mucci, N., Traversini, V., Giorgi, G., Garzaro, G., Fiz-Perez, J., Campagna, M., Rapisarda, V., Tommasi, E., Montalti, M., & Arcangeli, G. (2019, January 4). Migrant workers and physical health: An umbrella review. MDPI. https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/11/1/232

Mucci, N., Traversini, V., Giorgi, G., Tommasi, E., De Sio, S., & Arcangeli, G. (2019, December 22). Migrant Workers and Psychological Health: A Systematic Review. MDPI. https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/12/1/120

NHS. (2024, January 18). Treatment - Anorexia nervosa. NHS choices. https://www.nhs.uk/mental-health/conditions/anorexia/treatment/

Physical Health and Mental Health. Mental Health Foundation. (2022, February 18). https://www.mentalhealth.org.uk/explore-mental-health/a-z-topics/physical-health-and-mental-health

Statements | United Nations Network on migration. United Nations Network on Migration. (2025). https://migrationnetwork.un.org/statements

Upadhyay, L. (2023, May 4). Migrant workers in Lebanon: Healthcare under the kafala system. Médecins Sans Frontières(MSF)/Doctors Without Borders. https://msfsouthasia.org/migrant-workers-in-lebanon-healthcare-under-the-kafala-system/

World Health Organization. (2008). Closing the gap in a generation: Health equity through action on the Social Determinants of health - final report of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-IER-CSDH-08.1

Zahreddine, N., Hady, R. T., Chammai, R., Kazour, F., Hachem, D., & Richa, S. (2013, December 27). Psychiatric morbidity, phenomenology and management in hospitalized female foreign domestic workers in Lebanon - Community Mental Health Journal. SpringerLink. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10597-013-9682-7